Self-Defeating Life Patterns

December 24, 2025

How Self-Defeating Life Patterns Develop

“I won’t make the mistakes my parents made,” many of us say to ourselves as we launch into adulthood. With the natural optimism of youth, we apply our energy and strength to achieving “success” and “happiness.” Unfortunately, what we sometimes create instead are self-defeating life patterns that can sabotage adult well-being and success. These self-defeating patterns flow directly from childhood survival strategies, which we don’t stop until we’re locked in and they negatively affect our relationships and physical and emotional health.

Self-defeating life patterns derive directly from our childhood behavioral strategies:

- Taking responsibility and focusing on achieving can lead to compulsive achievement.

- Caretaking and controlling in relationships can lead to co-dependency. Robin Norwood originally described co-dependency in Women Who Love Too Much.

- Rebelling and being a lightning rod can lead to generalized rebellion.

- Adapting and becoming invisible can lead to casualty syndrome.

- Remaining dependent under-responsible may lead to under-responsibility pattern.

My name is Lane Lasater, a retired clinical psychologist. In gratitude for the life I have been given, I am sharing everything I learned during my career and personal life here on my website http://www.LaneLasater.com and on my YouTube Channel Life Roadmaps from a Retired Psychologist https://www.youtube.com/@lane205 Each post contains my written material, an AI generated graphic, a 15-17 minute audio summary, and a 5-7 minute video summarizing the material. A printable and fillable PDF “Exercises to Support Recovery from Family Trauma Syndrome” with each exercise I describe in my videos can be downloaded here: Transcending Family Trauma Workbook

“Growth is painful. Change is painful. But nothing is as painful as staying somewhere you don’t belong.”

Mandy Hale

Our Outdated Survival Patterns

These adult behavior patterns involve over-using our childhood coping mechanisms. How do these activities become self-defeating behavior strategies? Dr. Claudia Black points out that for each child survival strategy, we learn certain skills, but simultaneously neglect others (It Will Never Happen to Me). For example, if we learn to take responsibility and achieve, we may not learn to ask for help and trust. If we learn to be dependent or under-responsible, we may not learn how to take care of ourselves or follow through with commitments. Childhood patterns become self-defeating life patterns as we use the skills we have over and over, while neglecting other skills we need to develop. The wider the “skill gap” becomes, the more challenging it becomes to learn the skills we’ve unwittingly neglected.

There’s an ironic trait of human nature at work here. When a particular strategy doesn’t seem to work anymore, our first reaction is to use it even more frequently and more intensely. For example, when we encounter someone who doesn’t treat us fairly, we may become angry. When this doesn’t seem to change their behavior toward us, we become more aggressive and more demanding, perhaps shouting and making threats. Or, we may respond to mistreatment by being increasingly accommodating, failing to notice that we’re dealing with someone who isn’t acting in good faith. Recovery involves identifying our misguided strategies and substituting new behavior options, including the option to walk away from a situation or relationship that is toxic for us.

By early adulthood, our behavioral strategies and skill deficits have become established and habitual. Our choices become habits, these habits become our reality, and through this reality we define ourselves and the world. In this way, we become deeply invested in remaining the same, even if that means remaining in pain and conflict. Unfortunately, many of us conclude that unhappiness and conflict are normal and unavoidable.

As adults, we sometimes make broad statements about ourselves such as, “I’m good at getting things done, so I might as well do it myself,” or, “I’m afraid to tell him/her what I want because they’ll laugh at me,” or, “I don’t understand men (women),” or, “I hate being told what to do,” or, “I’m shy in new situations,” or “Why should I do it if I can get someone to do it for me?” We don’t question how these beliefs developed; we just assume that’s the way we are.

- Three factors explain why we perpetuate certain child behavior strategies into adulthood, where they progress into self-defeating life patterns.

- We have a mistaken belief (relating to childhood circumstances) that this behavior will lead to achieving our goals.

- Each behavior pattern leads to intermittent rewards that reinforce the pattern.

- Continuing our survival behavior helps us to avoid recognizing painful feelings and problems.

As self-defeating life patterns progress, we over-invest in these behaviors and under-invest in behavior that would help us meet other basic human needs. We may dimly recognize the psychological, physical, and interpersonal complications resulting from our choices, but because our strategies sometimes work, we hesitate to change. As we continue using our childhood survival behavior patterns, we create increasingly unbalanced adult situations.

For many of us who grew up in families challenged with trauma and addiction, one self-defeating life pattern may create the most problems, but some of us also have characteristics of other patterns. For instance, we may be compulsive achievers in professional life but behave according to under-responsibility pattern in an intimate relationship.

Five Self-Defeating Life Patterns

During the behavior change process in recovery, clarity means we understand exactly how specific problem behaviors and complications work, which enables us to address these one by one. Each self-defeating life pattern has four important characteristics:

The primary behavior that defines the pattern,

The central obsession that preoccupies us with this pattern,

The mistaken belief that perpetuates the pattern, and

The missing skills that make the pattern difficult to change.

Following the description of each pattern below, you’ll assess whether that pattern is a problem for you.

1. Compulsive Achievement

Primary behavior: involvement in sports, school, and work over sixty hours per week; considering one’s achievements as a primary identity; working to achieve when you need to spend time with family or friends; neglecting health or rest to advance personal goals.

Central obsession: thinking about, planning for, or worrying about achievement when not actively striving.

Mistaken belief: When I meet my next goal, I’ll be happy.

Missing skills: the ability to relax during unstructured time, and the capability to be emotionally close.

Under-Investing in Himself

“I know that my marriage is in trouble. My wife says I spend too many hours at work. I just don’t feel close to her anymore. She doesn’t seem to understand what I have to do to get ahead at my job and seems angry all the time.”

As a self-employed regional sales representative, Justin thought constantly about the money he made the more hours he worked. As a child, he’d struggled in school and felt humiliated. When he discovered his sales ability, it was a tremendous boost to his self-worth, and he devoted more and more time to succeeding. He began spent evenings and weekends making phone calls to lining up appointments.

The result of Justin’s overinvestment in work was underinvestment in his marriage and family relationships, in caring for his health, and in recreation. His business success was becoming meaningless because he’d neglected these other aspects of his life. He suffered from migraine headaches and stomach problems. As time went on, Justin became less able to withdraw mentally from thinking or planning for work. He couldn’t wait for the weekend to be over and get back on the road. He smoked two packs of cigarettes a day and relied on alcohol to unwind and fall asleep at night.

Justin’s mistaken belief was “If I’m successful in sales I’ll be happy!” Work provided self-worth, and recognition, status, and financial success. Justin’s childhood motivation was an unconscious statement to those who had humiliated him: “I’ll show you I’m somebody!” His constant activity allowed him to avoid feelings of emptiness and loneliness and distracted him from the increasing consequences of his compulsive achievement. The more desperate these consequences became, the more compelled Justin felt to offset them with even greater professional achievements.

Image 5 portrays the childhood decision of a compulsive achiever who denies himself other necessary aspects of life because of relentless striving.

Compulsive Achiever: It’s Sunday afternoon and the compulsive achiever is preparing diligently for the coming week. He feels sad at passing up weekend fun, but considers the demands of work too pressing to allow time for any frivolous activity. He’s making another payment toward the long-term price of compulsive achievement—isolation, fatigue, and deprivation.

Recovery Exercise #9: Compulsive Achievement Self-Assessment

If compulsive achievement is a pattern in your life, rate how the characteristics of the pattern apply to you. Use a 0-10 scale for each characteristic, where 0 = very untrue of me, 4 = moderately untrue of me, 6 = moderately true of me, and 10 = very true of me.

I engage in school, sports, and work over sixty hours per week.

My achievements are my primary identity.

I work, work out or study even when I know I need to spend time with family or friends.

I neglect my health or rest trying to achieve my goals.

I think about, plan for, or worry about achieving when I’m not actively working.

I equate happiness with my level of achievement.

It’s hard for me to relax during unstructured time.

It’s hard for me to be emotionally close.

Your Compulsive Achievement Score

The highest possible score on this self-assessment is 80. Single-item high scores or an overall score above 40 suggest you may have a problem with this pattern.

2. Co-Dependency

Primary behavior: investing time, energy, and affection in an intimate relationship with someone who doesn’t reciprocate equally; subordinating one’s own wishes, needs, and values to accommodate a partner; taking most or all the responsibility for the problems in a relationship; worrying more about the other person’s problems than he or she worries about him or herself.

Central obsession: thinking, worrying, or planning how to improve a relationship.

Mistaken belief: If I care for someone enough, they will care about me.

Missing skills: awareness of personal feelings and needs; ability to protect oneself from criticism or abuse.

Fear of Being Alone

Ashley was depressed, anxious, and angry and often sick. Her husband Rick didn’t reciprocate her caring. He frequently criticized Ashley and gave her little affection or attention. She extended herself more and more to please him, trying to be attentive and considerate of his needs, and tried to inspire him to be the romantic partner she wished for.

From time to time, Ashley became extremely frustrated and lashed out at Rick. In response to her explosions, he became attentive for a time, but then seemed to pull away even more. The possibility of losing Rick terrified Ashley, and in response to his distance, she would soon begin “caretaking” again.

As time went on, Ashley spent more time and energy preoccupied with and worried about her relationship. She encouraged Rick to read books or talk to their minister, but he wouldn’t follow through. She gradually withdrew from her friendships and social activities. She felt ashamed she didn’t have the loving relationship she craved. She comforted herself with junk food until she was 40 pounds overweight.

Ashley’s mistaken belief was, “I can love him enough to make him love and care for me.” Rick had grown up in a cold household and didn’t learn to be tender and giving. In the early phases of the relationship, he responded to Ashley, and off and on was sensitive and interested. Ashley lived for these intermittent rewards, but she was emotionally starving in the relationship.

The childhood motivation behind Ashley’s behavior was rejection by her father and determination to make another man “love me and see how special I am.” Her loneliness, anger, and fear frightened her because they triggered powerful childhood feelings of hopelessness and self-hatred. She tried desperately to make her marriage work in order to avoid facing painful reality.

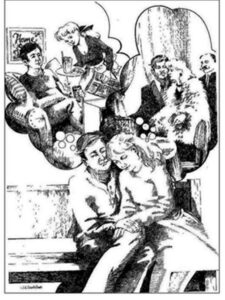

Image 6 presents the discrepancy between the romantic visions that couples may unknowingly carry into a love relationship.

His Dream/Her Dream: The romantic couple is lost in the euphoria of “being in love.” Each partner envisions a person who will fulfill their needs for attention and caring. His vision is of a woman who caters to his every wish. Her vision is of romance and an intimate life together. Both envision themselves receiving. Eventually, the discrepancy between their visions becomes apparent.

Recovery Exercise #10: Co-Dependency Self-Assessment

If co-dependency may be a problem for you, rate to what extent the characteristics below apply to you using the same 0-10 scale you used for the compulsive achievement self-assessment.

I invest time, energy, and affection in a relationship where these qualities aren’t reciprocated equally.

I subordinate my own wishes, needs, and values to accommodate a partner.

I take more than my share of responsibility for the problems in a relationship.

I worry more about another person’s problems than he/she does.

I spend much of my time thinking, planning, or worrying about how to improve the relationship.

I try directly or indirectly to change another adult’s feelings and behavior toward me.

It’s difficult to identify and express my feelings and needs.

I feel unable to protect myself from criticism or abuse.

Your Co-Dependency Score

The total possible score on this scale is 80. High single-item scores or an overall score above 40 suggest that you may have a problem with this pattern.

Generalized Rebellion

Primary behavior: engaging in uninvited attempts to influence people and organizations; frequently taking a scapegoat or “fall guy” role in group situations; taking responsibility for things that are not appropriately your concern; using gentler persuasion at first, then turning to more aggressive tactics when others do not respond.

Central obsession: outrage over the irresponsibility or misbehavior of people or organizations.

Mistaken belief: “My good intentions and efforts can overcome any problem.

Missing skills: ability to let issues pass without challenge if they don’t directly involve you; ability to disengage from people or situations you can’t change.

A Frustrating Campaign

“I’m so upset about work I can’t sleep. I took a job as an assistant manager in this office supply company a year ago. I was excited about the job but can’t stand the infighting and favoritism. They made a guy who started after me the manager for the evening shift. It drives me crazy!”

Joseph began a fruitless struggle to institute changes at work, even though some of his concerns weren’t his responsibility. People listened to his initial suggestions, but as time went on, they stopped listening and they considered him a troublemaker.

Because of his campaigns over various issues, Joseph didn’t fulfill his own duties completely, and it strained his relationships with other staff members. He took his work frustration home and had more conflicts with his family. He wasn’t enjoying life, and he spent evenings smoking, drinking, and watching TV.

Joseph’s mistaken belief was, “I know how things could be better here and I can bring these changes about if I try hard enough.” His intermittent success at instituting changes was rewarding enough to give him a sense of autonomy and self-esteem.

The roots of Joseph’s present struggle were in his childhood attempts to change his family. For years, he tried to change his parent’s conflicts and stop their arguments over money. His unconscious childhood resolve was “I’ll make my family change, no matter what!” As Joseph confronted his failure to change his place of employment, he recognized his long-standing frustration about his inability to help his family.

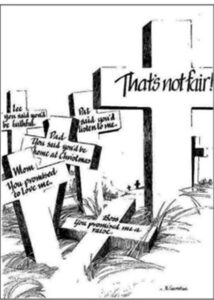

Image 7 portrays our long-term failure at changing painful realities that are not under our control.

The Lost Cause Graveyard: A graveyard is the appropriate resting place for many of the issues we fight in generalized rebellion. As adults, we unwittingly choose people and situations we were powerless to change, thus duplicating the limitations of our childhood environment. We can’t make other people and organizations be what we want and need.

Recovery Exercise #11: Generalized Rebellion Self-Assessment

Have you struggled with lost causes and situations you were powerless to change? If so, use the 0-10 scale to rate the extent to which the following characteristics apply to you.

I engage in uninvited attempts to influence people and organizations.

I take the scapegoat or “fall guy” role in group situations.

I take responsibility for things that aren’t appropriately my concern.

I use gentler persuasion at first and then turn to more aggressive tactics when others don’t respond.

I’m preoccupied with the irresponsibility or misbehavior of people or organizations.

I believe I can overcome any problem with good intentions and effort.

I can’t let issues pass without challenge, even if they don’t directly involve me.

It’s hard to disengage emotionally, even when it’s clear I can’t directly influence people and situations.

Your Generalized Rebellion Score

The total possible score is 80. Single high scores or an overall score of 40 or above imply that you have a problem with this pattern.

Casualty Syndrome

Primary behavior: taking part naively or passively in situations that affect your well-being; trying to get other people to take care of you; expressing hostility passively or indirectly; letting authority figures such as parents, professionals, or church authorities tell you what’s best for you.

Central obsession: preoccupation with how others have wronged you.

Mistaken belief: If I just do what is right, other people will as well.

Missing skills: awareness of your feelings and needs; ability to assert your wishes and rights.

Just Doing Her Job

“I feel defeated. I can’t cope with life. We moved to this town three years ago, after my father abandoned us. He was violent with my mother and older brother, and when she went to the safe house, he left us. Since that time, we’ve had a hard time getting back on track.”

Elizabeth was pale and showed little emotion as she described her life. She had responsibility after school for her three younger siblings, and she worked at a Quick-Stop that didn’t allow her to use her capabilities. After her father left, the family was in constant financial stress and her mother made things worse by spending money on furnishings they couldn’t afford.

Elizabeth tried to hold the family together, but her father had never fully accepted career and financial responsibilities, and turned to alcohol as an escape. Until her mother finally drew the line conflict, violence, and frequent crisis characterized their lives. The family lived on a roller coaster of financial challenges, conflict, and unhappiness. Elizabeth’s childhood hope was, “If I just go along quietly and do my part, things will turn out all right.”

Recovery Exercise #12: Casualty Syndrome Self-Assessment

If you feel victimized in a relationship or job situation, rate which characteristics of casualty syndrome you experience in that situation. Use the 0-10 scale.

I take part passively in situations that directly affect me.

I hope to find someone who’ll take care of me.

I let people know indirectly when I’m unhappy about something.

I allow authority figures in my life to tell me what is best for me.

I dwell on how people have wronged me.

I believe that if I do what’s right, other people also will.

It’s hard to identify my feelings and needs.

I don’t know how to assert my own rights and wishes.

Your Casualty Syndrome Score

The highest possible score is 80. Single high scores or an overall score above 40 imply that you may have a problem with this pattern.

Under-Responsibility Pattern

Primary behavior: not following through on your commitments; getting others to take care of your responsibilities; asking that people make allowances for you or your special circumstances or limitations; finding that others are often angry or disappointed in you because of your behavior.

Central obsession: trying to find an easier way.

Mistaken beliefs: If I can get away with it or get someone to do it for me, I might as well. You shouldn’t have to work too hard in life.

Missing skill: taking responsibility for oneself.

Charming His Way through Life

“My wife and I separated when she discovered I was having an affair for a year. I knew I had to stop seeing the other woman, but couldn’t break things off. Things aren’t going well in my business, either. I started it about three years ago and it grew faster than I expected. I overspent and got behind with the IRS. Now I can’t get out of debt.”

Jacob was an attractive and obviously talented person, and his charisma drew others to him. Many people had given him the benefit of the doubt in the past, but now their trust was wearing thin. Jacob’s pattern was letting things deteriorate before attempting to solve the problem. His new starts lasted for a short time before he’d neglect responsibilities and undermine his progress.

Jacob’s mistaken belief was “If I really try hard for a while, then I can relax.” As the youngest child in his family, his mother made excuses for Jacob and protected him from the consequences of his irresponsibility. He learned his charm would get him through. The intermittent rewards of being irresponsible came from other people tolerating his lack of follow through on commitments, at least for a time.

Jacob’s childhood decision behind this behavior came from with his relationship with his father, who didn’t push Jacob to achieve or require hard work and follow through. Jacob’s conclusion became, “I don’t have to push myself and can just do enough to get by.”

By the time Jacob went through his cycle many times, he felt intermittently desperate. He turned to sexual affairs to relieve his distress and as a result sowed the seeds of his next crisis.

Recovery Exercise #13: Under-Responsibility Pattern Self-Assessment

Do you have some characteristics of under-responsibility pattern? Rate which characteristics apply to you using the 0-10 scale.

It’s hard to meet my commitments.

I let other people take care of things that are really my responsibility.

People make allowances for me or my special circumstances or limitations.

I find myself in trouble with others because of my behavior.

I think about how to avoid the drudgery of life.

If I can get away with something or get someone else to do it, I might as well.

I shouldn’t have to work too hard in life.

It’s hard to take full responsibility for myself.

Your Under-Responsibility Pattern Score

The highest possible score on this scale is 80. Single high scores or an overall score of 40 or above imply that you may have a problem with this pattern.

Complications of Our Self-Defeating Strategies

Understanding how self-defeating life patterns apply to you gives you a clear focus for behavior change. Thinking about how each pattern may apply for you helps you be clear about your blend of these behaviors. This understanding will help you in moving from survival behavior to freedom.

This chapter described five people actively struggling with self-defeating life patterns which did not serve their best interests, but operated invisibly so they couldn’t readily identify where they were going wrong. Their lives illustrate common complications of self-defeating behavior strategies:

- Neglect of self-care, diet, and exercise

- Getting sick frequently

- Muscle tension and pain

- Shame, guilt, anger, or disappointment

- Depression, anxiety, or insomnia

- Family or marital conflict

- Work conflict

- Burnout symptoms such as cynicism, apathy, or fatigue

In future posts, I’ll help you evaluate the severity of these complications in your life and develop a plan to address these complications.