Overcoming Enduring Emotional Adjustments

January 4, 2026

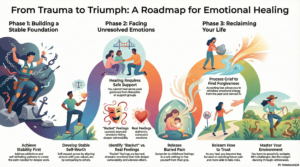

There’s still more to do in recovery because enduring emotional adjustments still detract from the quality of our lives. It’s difficult to leave addictions behind and change self-defeating life patterns fully until we face and overcome the unresolved childhood emotions which underlie these behavior patterns. We normally tackle addictions and self-defeating life patterns first because we need to stop creating fresh problems to achieve the calmness, self-awareness and focus necessary to face painful feelings from the past. This chapter describes the emotional healing process during recovery and guides you in maintaining your hard-won recovery gains.

My name is Lane Lasater, a retired clinical psychologist. In gratitude for the life I have been given, I am sharing everything I learned during my career and personal life here on my website http://www.LaneLasater.com and on my YouTube Channel Life Roadmaps from a Retired Psychologist https://www.youtube.com/@lane205 Each post contains my written material, an AI generated graphic, a 15-17 minute audio summary, and a 5-7 minute video summarizing the material. A printable and fillable PDF “Exercises to Support Recovery from Family Trauma Syndrome” with each exercise I describe in my videos can be downloaded here: Transcending Family Trauma Workbook

“It is by going down into the abyss that we recover the treasures of life. Where you stumble, there lies your treasure.”

Joseph Campbell

Developing Stable Self-Worth

Our self-worth stabilizes as we care for our inner self, stop addiction, and replace self-defeating life patterns. Recovery progress on these tasks translates readily into self-respect, because we’re living a life in alignment with our deepest values. Rather than beginning each day with remorse, shame, or fear, we wake up feeling positive because we regret nothing we did yesterday and behaved in ways we feel good about. We don’t attain 100 percent improvement, but acknowledge and celebrate our progress.

When you make your best effort, you can accept your personal rate of growth. Sometimes your progress may seem slower than someone else’s, but this usually means you had more to overcome, or faced greater deprivation or trauma. Your recovery path is unique. To appreciate your progress, compare yourself to your own past. Review your recovery journal from time to time, and you’ll see how you’ve grown.

As children, unstable self-worth was a way of defending against hurt or disappointment by lowering our expectations. Now we no longer must prepare ourselves for the worst by putting ourselves down and feeling unworthy. Ironically, we discover our greatest trials can become sources of wisdom and strength when we see them through. Our new capacity to be who we are and honestly share the truth of our lives has a powerful effect on family members, friends, employers, and employees.

People respond to our compassionate honesty with trust, feel safe to confide in us, and we realize we have new personal experience and wisdom to share. We transition gradually from humiliation to humility. Humiliation is the person-destroying experience of unworthiness, failure, and shame. Humility is an honest self-respect that incorporates the awareness we’ve made mistakes in life, learned from them, forgave ourselves, and moved on. We’re fully human.

Healing Unresolved Emotions and PTSD

During recovery from family trauma and PTSD, we must face sometimes overwhelming childhood memories. To confront these feelings, we need the help, support, and guidance from people who know the way through. Powerful childhood feelings can often arise suddenly, such as when we encounter an authority figure who criticizes us, and we plunge into feeling profoundly ashamed, humiliated, and vulnerable from long-forgotten childhood moments. Being plunged into “childhood consciousness” can devastate us when we don’t realize what’s happening to us, and we momentarily lose access to our adult skills and awareness. In the past, experiences of childhood pain often drove us again and again back to addiction. It feels as if we can’t survive such extreme distress, but keep in mind the recovery saying, “This too shall pass.”

When we’re hurt, a common instinct is to push other people away, but we can’t heal well alone and in fact we need kindness and safety. Surrendering to vulnerable emotions like grief in the presence of loving and supportive people is transforming. When we take risks with safe people (in support groups, for example), we can receive the unconditional positive regard we yearned for, and experience tenderness, forgiveness, peace, love, and joy.

We learn, “it’s impossible to look good and recover at the same time,” and thankfully, we don’t have to. Here are some difficult emotional states you may visit in recovery, but these are necessary markers on your path to freedom.

- I can’t stop crying.

- I’m in a black hole.

- I’m swimming through molasses.

- I’m caught in quicksand.

But eventually we arrive at:

- I feel on top of the world.

- I’m grateful to be alive.

- I’m more compassionate because of what I’ve been through.

Real Feelings vs. Racket Feelings

In our families, we learned certain negative feelings were acceptable and others not. So Mary and Robert Goulding point out we practiced the kinds of negative feelings allowed at home (“Changing Lives through Redecision Therapy”). Because we overlearned these permissible forms of emotional expression, they became “racket,” or sham feelings that we unwittingly used to manipulate others. Some families were “anger” families and others were “victim” families, or “guilt” families. Adult racket feelings often appear dramatic because we’ve practiced them, but they cover deeper vulnerability and alienate people who witness them. “Anger” people are good at blaming others, “victim” people are good at being wronged and helpless, and “guilt” people blame themselves and apologize all the time.

These racket feelings backfire in adult relationships. Frequently, “anger” people really feel hurt, ashamed, and afraid. When they express racket anger, other people pull away, and they feel more alone and hurt. “Victim” people often feel helpless and hurt, but when they play the victim, it turns people off, who may then mistreat them more. “Guilt” people often want acceptance and love, but when they express racket guilt, people reject them and consider them weak. Thus, racket feelings become just another ineffective childhood survival pattern.

Once we understand what our “racket programming” is, we practice expressing genuine feelings. We can recognize someone else’s racket feelings because we see the drama but feel repelled rather than drawn to them. Group therapy is a powerful tool during recovery because people can compassionately point out to us when they sense racket emotions and help us discover the more vulnerable emotions that underlie these defenses.

Our recovery task, once we get beyond racket feelings, is sharing our story with genuine emotion with people who care. We can momentarily surrender to overwhelming childhood feelings in safe settings, cry our tears or express our anger, hurt, or shame while harming no one. This emotional release frees us to move on with our lives unencumbered by this childhood pain.

As we recover, we understand we got stuck along the path of normal development and have a hurt, frightened, or angry little boy or girl hiding behind our adult facade. We revisit painful events of childhood or earlier adulthood, recognize our discounted feelings, and bring those hurts and traumas to new, functional endings. This opens new behavioral and emotional freedom, and we look and feel like different people.

Facing Abandonment

In group therapy, Melissa asked for help with her angry feelings about a violent incident in her stepfamily when she was eight. She described the dramatic family scene, but members of the group were restless. Several people pointed out to Melissa that they weren’t connecting to any genuine feeling. Melissa had unconsciously chosen to talk about something that seemed impressive, but had no emotional connection for her.

Melissa felt ashamed after this feedback, but it spurred her to remember a time after her mother died (when Melissa was three) when she lived with an aunt and uncle who resented her. She asked a woman from the group to role-play her mother for a few moments so she could say goodbye. The entire group cried as the abandoned little girl sobbed in her mother’s arms. By the end of the evening, Melissa, who had appeared very young for her nineteen years, seemed older and radiated a new calm and confidence.

Re-Experiencing Traumatic Events

Earlier, I described multi-dimensional experiential psychotherapy and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) as two useful trauma resolution resources. One reason for some past recovery treatment failures was because purely verbal approaches were ineffective for people who’ve experienced traumatic events. Just talking about what happened didn’t touch buried and frozen feelings.

After we establish a foundation of recovery, including stopping addiction, we can face traumatic memories from our past while retaining our adult power and the support of a loving group or the safety of individual psychotherapy using EMDR. In these specialized settings, we can experience exactly what it was like for us as children, release anger and sadness, comfort our terrified or abandoned child-selves, and rescue them forever from the scenes that haunt them.

Release of Hatred

As a boy, his mother badly beat Christopher. When he was older, he emotionally punished women he dated. He felt remorse after he rejected or said mean things to his girlfriends, but he hadn’t been able to stop the pattern. In a psychodrama group, Christopher re-created the scene in which his mother lost control and beat him until he was unconscious after he broke a window in a neighbor’s house.

When Christopher re-enacted being beaten in his group (harmlessly, of course), he remembered his terror and hatred. He released his terrible anger at his mother by beating on pillows, shouting, and crying until he spent his anger. Then Christopher held a fantasy conversation with his mother, who was now dead, and for the first time could see within her the overwhelmed little girl who was herself abused as a child. With his anger and hurt behind him, Christopher’s heart softened and he could forgive her at last. In his later relationships, Christopher had to self-consciously practice loving behavior with women, but this past trauma no longer indirectly controlled his life.

Facing Grief

To arrive at forgiveness and love despite the events of the past, we must experience our losses and process our grief. William Worden describes four tasks of grief (Grief Counseling & Grief Therapy):

- To accept the reality of the loss

- To experience the pain of grief

- To adjust to an environment in which what we lose is missing

- To withdraw emotional energy and reinvest it elsewhere

These tasks apply specifically to grieving a death, but they also pertain to the grief we feel, whether other family members are living or dead, that our families weren’t the way we needed them to be. We recognize the reality of our losses, seeing clearly and compassionately how things went right or wrong as we grew up. As we recognize what the costs have been to ourselves and to those we love, feelings of grief naturally arise. We recognize the tragedy and waste of lives that so often accompany traumatized families, including family members who couldn’t overcome their addiction and other destructive patterns, and died or committed suicide. We’ll always feel sadness over what could have been but never happened, but our regret doesn’t sink us or prevent us from going on to happiness and fulfillment.

We adjust to our losses by adding into our lives people and resources who give us back some of what we missed. We naturally withdraw emotional energy from our childhood families and invest it in our love relationships, careers, friends, and our own children. If we become parents, we discover how easy it is to make mistakes when parenting, and our compassion for our parents increases. We become ready to forgive. There are certain prerequisites for forgiveness.

- Grieving the loss and recognizing both our pain and anger

- Taking responsibility for our own part (if any) in what happened

- Discovering that we can go on with our lives

- Recognizing the mitigating factors (if any) that explain other peoples’ behavior

- Understanding that our own lack of forgiveness wounds us

- Realizing that we also need forgiveness

By the time we experience and understand these steps of grief and forgiveness, we arrive at gratitude. As our hurt and anger fade, we remember and appreciate the good things that happened. As we learn more about our parents’ childhoods and lives, we usually see that they gave us more than they received. We can’t help but love them. However wounded we were, we survived.

Beginning to Trust

We sometimes lived in perpetual states of fear and insecurity as children. Further childhood wounding might have placed us in emotionally impossible positions, so we behaved as we do when we’re physically hurt—constantly aware of being wounded and moving carefully to avoid further pain or damage. Emotionally, as children, this often meant not letting anyone get too close and avoiding vulnerability because we feared rejection, or rejecting others at the first sign of conflict or difference to avoid abandonment. As we heal from hurts of the past, we become less preoccupied about avoiding future hurts. We regain the capacity to face painful losses that may lie ahead for us and regain our capacity to take risks.

As we progress in recovery, we gradually overcome our distrust of ourselves, others, and the world. We consciously decide to make ourselves vulnerable in therapy or support groups, recognizing that our efforts to solve our problems alone have failed. We discover there’s a better way. As children, not trusting was a way of protecting ourselves from greater losses than we could sustain. Our conclusions that other family members and our environments were unpredictable or untrustworthy were unfortunately often accurate, but we are no longer trapped in this way.

During recovery, we sometimes fear we won’t continue to grow and learn. We get spooked that things are going too well and our old defenses come into play. We’re tempted to pull the roof in on ourselves to avoid the disappointment of some unexpected disaster. Our addiction may tempt us back, and we’re tantalized by the possibility of throwing away the recovery gains we have achieved. These are times when we must continue those daily recovery activities we know we need and avoid potentially destructive choices by just doing nothing until we feel more centered. When life trials overtake us, we draw upon our carefully built up “spiritual bank account” to help us make sane choices.

Dealing with our Childhood Families

Many of us enter recovery before other members of our childhood family get help. Some family members never get involved in recovery, while all members of other families seek help, attend self-help groups, and take part in family therapy to heal together. There’s seldom a perfect match of different family members’ needs, feelings, and behavior. Our recovery may involve being emotionally and physically apart from families that don’t understand or support our efforts. Parents and siblings often fear that family secrets are being shared in distorted and unfair accounts (which they may be). Recovering parents find it hard to watch their adult children still suffering from childhood wounds and floundering while the parents pursue recovery.

The ironic truth of recovery is that when we stop trying to change or influence other family members and focus on ourselves, they may start changing. This almost never happens on our timetables and often requires further growth and new tolerance from us. Only after we’ve achieved substantial recovery for ourselves can we seriously consider attempting to help the people we love, who remain trapped in their own self-defeating strategies.

It’s almost always best to wait until someone asks for help. Acting too soon by trying to force family members to change then becomes a familiar and destructive replay of our old expectations of other family members. Neutral people are usually the most effective messengers who family members can listen to, and emotionally uninvolved professionals are a tremendous help if you attempt an intervention for another person.

We couldn’t trust our own feelings as children because we didn’t have knowledge and support, but now we have adult information and life coping skills. Self-help groups let us observe people like us who confront, struggle through, and overcome their life challenges.

Sometimes we feel grateful we don’t have to walk in their shoes, but they show us it’s possible to maintain recovery in the face of anything—death of a spouse, terminal illness, troubled children, divorce, death or illness of a child, bankruptcy, imprisonment, or unemployment. As we overcome our survival patterns, we find we can master setbacks in life that previously would have sapped our energy and joy.

Image 12 portrays this mastery.

Dancing through the Rattlesnakes This cowgirl is the master of her environment, gracefully skirting the rattlesnakes that surround her.

Key Takeaways from this Chapter

- Your foundation of recovery from addiction and self-defeating life patterns provides the stability, calm and focus you need to face powerful feelings from childhood experiences

- We restore self-worth gradually when we’ve stopped (or at least slow down) creating external problems for ourselves and behaving in ways we regret while taking positive actions at the rate we’re able that leave us with new self-respect

- Fortunately, there are a multitude of self-help and recovery therapy resources to provide safe places to experience powerful emotions and release them without harming you or anyone else

- Carefully choose people as recovery allies who have themselves walked this path, and they can provide the guidance and safety required to connect with and restore your wounded child self

- Relationships with your childhood family naturally change as you access new resources and grow. Always focus on following your recovery path, which may require some apartness from family members who feel threatened by your choices or are unsupportive