From Escape to Addiction

December 24, 2025

Childhood Self-Comforting Strategies can Lead to Addiction

This post describes how addictions develop from our childhood coping mechanisms.

As human beings, we naturally seek changes in consciousness. Achieving a satisfying and lasting state of mind and body is a basic life challenge. Our feelings and awareness can change subtly or dramatically, sometimes rapidly and sometimes gradually. We achieve subtle changes in consciousness by taking a hot shower in the morning, eating a delicious meal, completing a project at work, watching a beautiful sunset, working out at our health club, or playing with children in the evening. More dramatic changes in consciousness come from drinking alcohol, using drugs, over- and under-eating, having sex, risk taking, or gambling.

The more distress we experience, the more likely we are to seek distinct and immediate changes in consciousness. These behavior patterns become addictive when we choose them over and over until we feel unable to stop, even when we harm ourselves or others. Our addictive escapes create significant new emotional, health and relationship problems.

My name is Lane Lasater, a retired clinical psychologist. In gratitude for the life I have been given, I am sharing everything I learned during my career and personal life here on my website http://www.LaneLasater.com and on my YouTube Channel Life Roadmaps from a Retired Psychologist https://www.youtube.com/@lane205 Each post contains my written material, an AI generated graphic, a 15-17 minute audio summary, and a 5-7 minute video summarizing the material. A printable and fillable PDF “Exercises to Support Recovery from Family Trauma Syndrome” with each exercise I describe in my videos can be downloaded here: Transcending Family Trauma Workbook

“Addictions represent misguided spiritual yearning.”

Unknown

Potential Addictions Are Everywhere

Emotional, biological, family, and cultural factors all contribute to the development of addiction. For many of us, pain resulting from enduring emotional adjustments and self-defeating life patterns increases the probability that we will seek relief through escapes. Families, communities, and society all teach us about different escapes. Our parents modeled “appropriate” escapes, and as children and teenagers we made discoveries about escapes, and society bombards us with glamorized addictions.

Our individual well-being from birth onward reflects the influence of a multitude of factors as psychology and biology interact. Three psychobiological factors normally contribute to the start of addictive behavior.

We experience a state of mind or body (usually negative) that we decide (consciously or unconsciously) to alter.

We discover a substance or behavior that “improves” that state of mind or body.

The consequences of this behavior commonly aren’t immediately severe.

Drinking to Addiction

His physician referred Greg to alcohol treatment because his drinking had led to pancreatitis. Greg was unhappy and worried after moving to a new community and said he’d always had a hard time dealing with change. He also reported he’d felt depressed most of his life.

Greg described his father as an unhappy beer drinker who was bitter and withdrawn. He didn’t spend the time with Greg that his son needed. Greg’s mother was unhappy about her husband’s passivity and dissatisfied with the family’s finances. Greg’s grandfathers on both sides were alcoholics. Because of negative childhood experiences around her father’s drinking, his mother didn’t drink at all.

Greg felt awkward with and intimidated by girls as a teenager, but felt confident when he drank. His humor and antics at parties gained acceptance from friends, and alcohol became a staple of his social life. In college Greg binged frequently and often passed out. After an arrest for drunk driving, he attempted to drink moderately, but failed as a social drinker. His doctor told him he’d have to stop drinking altogether because drinking was leading to severe health consequences.

Finding a Favorite Escape

During adolescent and early adult experimentation with different escapes, we often discover and “fall in love” with an escape or substance that offers dramatic and positive changes in consciousness. Favored escapes create biological/neurological interactions that we experience as “just right.” Then, we learn we can suppress feelings of loneliness, anxiety, depression, inadequacy, or shame and feel euphoric instead. We describe our escape experiences in enthusiastic terms, such as, “I feel confident and powerful when I drink,” “When I parachute, I feel really alive,” or “Eating ice cream, I feel peaceful and content.”

Adult escapes often flow from our satiation, arousal and fantasy childhood self-comforting strategies described by Milkman and Sunderwirth (Craving for Ecstasy). Using alcohol, taking tranquilizers, overeating, and spending are satiation behavior patterns. Cocaine, amphetamines, risk taking, gambling, cigarettes, and sexual seduction and masturbation are arousal behavior patterns. Marijuana, television, movies, and romantic novels are fantasy behavior patterns. During recovery, we must learn to replace our addictions one by one, stopping those causing the most damage first.

A Cycle of Eating, Purging, and Fantasy

Renee’s father was in the army, and the family moved frequently while she was in grade school. She hated to leave her friends and try to fit into a new school and often felt fearful and lonely. Renee created a fantasy world where she was surrounded by people who loved her.

Her parents fought bitterly with each other when Renee was little, and she learned later her father had had many sexual affairs. With Renee, her father was distant and critical. Her mother was overweight, and when Renee felt insecure or discouraged, her mother often offered her baked goods to eat. Renee associated eating with security amid painful events. Her habit was taking snacks from the refrigerator and retreating to her room with her books and drawing.

As a teenager, Renee ate to comfort herself, but was ashamed of her weight gain. She spent her free time reading romantic novels and dreaming of a relationship with a perfect lover who would make her the envy of everyone. To avoid gaining weight, Renee induced vomiting to rid herself of food from her binges. By adulthood, she felt trapped in a secret cycle of distress, eating, fantasy, guilt, vomiting, and depression. Recovery for Renee began when she sought help to stop bingeing and purging. With support, she could face her underlying loneliness and pain.

Your Vulnerability to Addiction

Many people use potential escapes without becoming addicted—why not me? Addictions don’t strike randomly—some of us are more vulnerable than others. You may drink to numb uncomfortable feelings like depression, anxiety, loneliness, social awkwardness, and daily stress, or you may use other mood-altering substances or behavior to distract you from unfinished feelings from childhood or earlier adulthood.

Unstable self-worth, unfinished feelings and PTSD, self-defeating life patterns, and family genetic risk factors all increase your vulnerability to addiction. The higher your risk, the more likely it is you could become addicted to alcohol, other mood-altering substances, overeating, gambling, sexual encounters, or other addiction. To overcome any kind of addiction, most of us benefit from general knowledge and information about recovery, as well as guidance specific to each addiction. Self-help groups for most behavioral and substance addictions are widely available. I describe addiction recovery resources and tools in a later post.

Some people in recovery describe addictions as, “misguided spiritual yearning.” This refers to feeling euphoric, peaceful, and connected to others when you’re under the influence of a chemical or a behavioral addiction pattern, but these feelings fade away when you come down, and we often crash emotionally and/or physically to the exact opposite of the euphoric feelings we sought. The uncomfortable neuro-physiological truth is “for every high there is an equal and corresponding low.” During recovery, we gradually learn how to feel content and connected to others without resorting to chemical or behavioral addiction.

Your genetic vulnerability to addiction may get triggered through the build-up of unfinished feelings, depression or anxiety, unstable self-worth, or traumatic life experiences. As research on addiction advances, we learn more about how each of these factors contributes to individual addiction risk. Estimating how vulnerable you are to addiction helps you make informed decisions during your recovery.

Recovery Exercise #14: Your Vulnerability to Addiction

Answer the following questions at two time periods in your life: (1) how things were (or are) for you at age 16, and if you’re older than 16, (2) how they are for you now. Use a 0-10 scale where 10 means very true of you.

I don’t respect myself.

Things from my past bother me.

It’s hard to trust other people.

I don’t take good care of myself with rest, diet, and exercise.

I get sick frequently or have pain and stress-related problems.

Depression, anxiety, anger, or insomnia are a problem for me.

Family conflicts bother me.

I have conflicts with friends, peers, employers, or co-workers.

It’s hard to meet my responsibilities at home, work, or school.

I’m bothered by shame, guilt, regret or disappointment.

I’ve faced traumatic experiences in my life.

One or both of my parents were addicted to a substance or behavior.

I drank, used drugs, overate, or used other escapes at an early age.

I get in trouble, do self-destructive things, or make poor decisions around escapes.

There are addictions and/or emotional or mental health issues in my family tree.

Understanding Your Score

Possible scores on this scale range from 0 to 150. A score of 40 or less suggests that you have low vulnerability to addiction, scores of 50-80 suggest moderate vulnerability to addiction, scores of 80-120 suggest high vulnerability to addiction, and greater than 120 shows extreme vulnerability to addiction. Even if your overall vulnerability score is low, one or more high scores on the questionnaire could imply higher vulnerability.

Your total score at age 16 vs. your score now shows you how your risk may have increased or decreased. If you have high or extreme vulnerability to addiction now and are already addicted to a substance or behavior, it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to engage in any mood-altering substances or behavior without risking another addiction.

How Addictions Develop

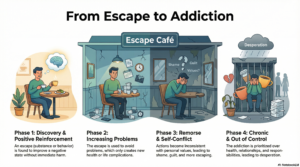

There are four phases in the development of addiction:

Phase One: We discover an escape pattern we like. Once we learn about drinking alcohol, taking drugs, eating our favorite foods, having sex, going on spending sprees, taking physical risks, or other escape behavior, we frequently discover these actions feel good and don’t have immediate unacceptable consequences. So, we turn to them again and again. We learn to rely on our addiction to achieve predictable changes of consciousness (Vernon Johnson, “I’ll Quit Tomorrow”). As we become addicted, we have hundreds or sometimes thousands of experiences with these substances or behaviors, and rely on them psychologically and physically to cope with life. Although the consequences of our behavior patterns are often minimal initially, they often steadily accumulate.

Hooked on Running

Danielle was ashamed of her parents, who were both overweight. Her childhood resolve was to never become fat. As a freshman in high school, she joined the cross-country team and discovered she loved running. She continued running year-round and competed frequently in races and marathons.

Her husband was also an athlete and liked to stay in shape, but he didn’t have Danielle’s zeal. He felt she was overdoing it with her ten-mile daily runs, but it fascinated Danielle to push herself to her physical limits. She continued running even though she developed a chronic problem with one knee. If she missed a workout, she became extremely irritable.

A medical evaluation identified addictive exercising as a probable factor in Danielle not being able to conceive. Even though her running now seemed to hurt her health, Danielle found it extremely difficult to slow down. Running had become an addictive behavior pattern. Danielle had to let go of her quest for physical perfection to begin recovery.

Phase Two: Our problems and pain increase. On top of whatever problems we faced before we adopted our addiction, we create additional problems for ourselves in two ways: (1) we use a substance or escape behavior instead of taking action to solve our day-to-day problems; and (2) our addiction eventually leads to additional complications.

Flying High

Brent came home from school every day angry about a domineering coach. He couldn’t stand up to this person, but when he smoked marijuana, it ceased to bother him. When he was stoned, school issues seemed less important, and he could relax and enjoy the evening. On weekends, Brent retreated to his hobby of riding his motorcycle. Risk taking became a way to affirm his independence.

Brent’s anger increased until he felt ready to drop out of school. His parents worried about his marijuana use and were angry that he neglected his school work. When his mother criticized him, Brent would explode, venting his pent-up frustration about school on her.

Phase Three: We feel remorse over our actions. When we turn to an addiction over and over, our actions become self-defeating and inconsistent with our personal values. We erode our self-worth and create additional shame and regret, which leads to more escaping. Ultimately, we feel unable to stop our addictive behavior, even when we face significant consequences.

Shopping into Debt

To comfort herself about not having a boyfriend, Angela spent all her money buying clothes. Her parents had emphasized frugality, but Angela rebelled, telling herself that she needed to be stylish in order to compete professionally and socially. Over a two-year period, she spent all her savings. Even though she earned a good income, she was always broke. She resolved to stop spending money until she caught up—but the next time she felt depressed and lonely; she went on a shopping spree. Angela stopped using credit and asked a trusted friend to monitor her spending in order to start recovery.

Phase Four: Escaping becomes chronic. As time goes on, we prioritize escape behavior over personal values, health, relationships, and job responsibilities. Health problems, remorse, depression, or family conflicts often increase until we feel out of control and desperate.

Prisoner of Sex

Nick’s father had extramarital affairs while Nick was growing up. When Nick learned of these as a teenager, he became very disillusioned. He felt outraged about his father’s betrayal of his mother and resolved never to do that in his own marriage. However, Nick learned covertly that to be masculine was to be a ladies’ man.

In college, he discovered he loved the challenge of making sexual conquests. He liked his reputation as a womanizer with his male friends. He saw himself as “sowing wild oats,” but his relationships didn’t last, and he would lose interest after the romantic phase of each affair. He began masturbating frequently while watching pornography.

When Nick contracted syphilis from a sexual encounter, it shocked him and it was humiliating to have to report to the health department. He recognized that sex had taken over his life. He didn’t know how to have an enduring relationship, yet wanted marriage and a family. Nick’s craving for sex had become a trap. He had to abstain from pornography and casual sexual encounters and learn to be intimate in other ways without the highs of a series of partners and pornography.

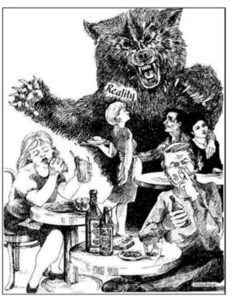

Image 8 portrays the crisis point in addiction, when accumulating problems threaten us with disaster. It portrays four addictions: alcohol abuse, cigarette abuse, food addiction, and addictive sexual behavior.

Last Supper at the Escape Café: Each cafe patron turns to his or her chosen escape for comfort, momentarily unaware of the looming disaster of genuine problems that will soon destroy this refuge.

Evaluating Your Use of Escapes

As a first step in recovery, identify which escapes (if any) have become addictive for you and don’t serve your value system and best interests. The higher your addiction risk score, the more cautious you must be with any potentially addictive behavior. If you have a low addiction risk score, that’s great, and means you have can devote your energy and time to other dimensions of recovery.

Destructive Escapes

Escapes that are illegal, involve physical risks, risk money you can’t afford, or have high addictive potential are clearly dangerous. If you use street drugs, take part in other illicit activities, gamble or pay someone for sex, you risk legal and health consequences, humiliation, and lost self-respect. Binge-and-vomit eating cycles, excessive fasting or extreme diets, death-defying activities such as rock climbing without ropes or wingsuit flying, ignoring safety procedures in parachuting, kayaking, or scuba diving, dangerous driving; and driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs are all obviously hazardous. Some people can smoke cigarettes occasionally without apparent harm, but most of us who start smoking become addicted with all the accompanying health risks.

If you use destructive escapes, ponder the price you’re paying and the risks you run. The following questionnaire helps you determine if a substance or behavior has become addictive for you. During recovery, you replace addictions, one by one, with positive, self-fulfilling behavior.

Recovery Exercise #15: Your Use of Escapes

Use a 0-10 scale for each statement about each escape behavior or substance use in your life, where 0 = very untrue of you, 4 = moderately untrue of you, 6 = slightly true of you, 8 = moderately true of you, and 10 = very true of you. Potential escapes include alcohol and/or drug use, food use, sexual behavior, exercising, spending, risk taking, gambling, or _________________.

My Use of Escapes

__________________is a problem in my life.

I obsess about and look forward to ______________.

I behave in ways I regret when I ______________.

I ______________to avoid negative feelings.

I attempt to change my ________________and fail.

Your Scores

A score of 24 or more for a particular behavior pattern or a single item high score implies that you may have a problem with that escape pattern. If you have one or more addictive behavior patterns, you’re not alone. In future posts, I describe resources for recovery, how to develop your recovery plan, and suggest guidelines for replacing addictions. Every step forward in recovery counts, so keep the faith!