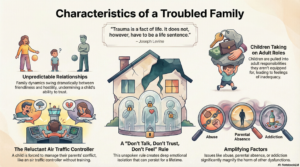

Characteristics of Troubled Families

December 19, 2025

Where Survival Strategies Originate

This post gives you an overview of how our childhood trauma and survival strategies in troubled families where we may have experienced insecurity, distrust, volatility, criticism, conflict, and distance. In many families, problems were hidden or invisible. These hidden family troubles are quite damaging because children don’t have dramatic events to explain feelings of distress. Robin Norwood (Women Who Love Too Much) and Dr. Charles Whitfield (Healing the Child Within) identify common characteristics of troubled family environments that gave rise to adult problem behaviors in their books. Here are frequent qualities I have observed in my own and other troubled families.

My name is Lane Lasater, a retired clinical psychologist. In gratitude for the life I have been given, I am sharing everything I learned during my career and personal life here on my website http://www.LaneLasater.com and on my YouTube Channel Life Roadmaps from a Retired Psychologist https://www.youtube.com/@lane205 Each post contains my written material, an AI generated graphic, a 15-17 minute audio summary, and a 5-7 minute video summarizing the material. A printable and fillable PDF “Exercises to Support Recovery from Family Trauma Syndrome” with each exercise I describe in my videos can be downloaded here: Transcending Family Trauma Workbook

Central Challenges in Troubled Families

“Trauma is a fact of life. It does not, however, have to be a life sentence.”

Joseph Levine

- Relationships were unpredictable and contradictory. Relationships in our troubled families often varied dramatically between friendliness and hostility. This included relationships between parents, between parents and children, and between siblings. As children in such families, we found ourselves unable to predict or understand sudden and dramatic shifts in behavior and mood. This undermined our security and ability to trust. A common harmful dimension of unpredictable and contradictory relationships was “psychological abuse,” when a parent with character disturbance and/or mental illness sometimes consciously and sadistically manipulates and oppresses a child. Shannon Thomas LCSW describes recovery from psychological abuse in depth in her book (Healing from Hidden Abuse).

Caught in the Middle

Stephanie couldn’t rely on being close to either parent for long. Because Stephanie reminded her mother of herself as a girl, her mother was sometimes close and inviting and sometimes critical and cold. Her mother didn’t support Stephanie as a teenager when Stephanie was vulnerable and needed compassion. In addition, her mother resented her husband’s affection for Stephanie, and Stephanie felt she needed to hide her love for her father. He would then pull back, and Stephanie felt doubly abandoned.

- Children took adult responsibility. Murray Bowen pointed out that children in troubled families are often assigned to or pulled into adult roles (Family Therapy in Clinical Practice). As children, we lacked the maturity, knowledge, and experience to assume emotional or practical responsibility for other family members, especially parents. Yet, if we perceived that a parent or both parents needed our help, we did our best to make things better by counseling the adults, or becoming an emotional surrogate husband or wife. No matter how well we may have carried out our “adult” responsibilities, we often came away feeling inadequate. In addition, these responsibilities interrupted our normal developmental tasks.

Trying to Fill His Father’s Place

Joshua’s father was away a great deal pursuing his career, and Joshua, as the eldest son, became an emotional confidante for his mother. She used Joshua to make up for the lack of support and intimacy she felt in her marriage. Because of their closeness, his mother made excuses for Joshua’s school failures and irresponsible spending. Joshua didn’t learn to be fully responsible, and his father was extremely critical about this. Joshua felt rejected, but couldn’t be close to his father, even though he needed guidance and modeling.

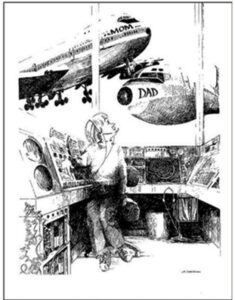

Image 2 portrays one dilemma of a child taking on adult responsibility in a troubled family.

The Reluctant Air Traffic Controller: As children, many of us faced challenging family situations we couldn’t handle. We had no choice but to do the best we could to cope with these situations. Here, a child tries to intervene in her parent’s conflict without the support, training, understanding, or maturity to take on this very challenging situation. We may have done a competent job in our family, even without resources, but because we lacked real readiness, we always felt anxious and inadequate.

- Affection and supervision were inappropriate. Some of us, like Joshua, received too much protection, so it inhibited us from developing our own autonomy and responsibility. Others received too little affection and supervision and felt unloved and emotionally deprived. Extreme styles of affection sometimes coexisted within the same parent or parent figure. A parent or older sibling would be affectionate one moment and harsh and angry the next. This inconsistency created an unpredictable and unmanageable childhood environment.

Rejected as a Person

As an adopted child, Rachel felt like an object rather than as a person. When her actions pleased her mother, she was affectionate, but when Rachel went against her mother’s authority, her mother rejected her coldly and reminded her she was fortunate to be living in this family. Rachel felt her role was as a showpiece rather than a unique and valuable person. She brought her deep loneliness and need for affection into adulthood. She feared her romantic relationships would never work because in her neediness she looked for a man who could make up for the love she’d missed.

- We felt emotionally isolated in our families. Dr. Claudia Black (It Will Never Happen to Me) points out that many families have the implicit rule of, “don’t talk, don’t trust, and don’t feel.” The result was emotional isolation, and we hesitated to talk to anyone outside our family because there was so much we couldn’t talk about. This isolation and distrust remain with us.

Family Secrets

Michael’s family had a reputation as a “super family” in his community. The children were highly visible and recognized for both academic and athletic accomplishments. Their home life was a different story, with his mother drinking and his father sometimes suicidal. These family “secrets” were hidden because Michael’s father viewed them as evidence of weakness. Secrets added up as the years went on, and Michael couldn’t tell his parents he was transsexual. He had reason to fear they wouldn’t accept what they would see as a flaw in the family image.

In combination with the above qualities in many of troubled families, other circumstances often aggravated the impact on children and further limited our opportunities to meet basic human needs.

- There was verbal abuse or physical violence at home. Family verbal abuse or physical violence added significantly to our fear as children. Violence magnified the impact of other destructive factors. The emotional and physical violence some of us encountered included hostile silences, deliberate failure to respond to others’ requests, putdowns or sarcasm, name calling and humiliation, intimidation, breaking things, dangerous driving, harsh spanking, pushing, shoving, slapping, and hitting, and, at the extreme, assaulting others with objects, knives, or weapons.

From Abuse to Passivity

Lauren’s father beat her mother, who slapped and hit Lauren, particularly as a teenager. Lauren’s attractiveness seemed to threaten her mother, who found fault with all Lauren’s achievements. When Lauren rebelled, her mother became enraged, and Lauren feared her physical assaults. She learned to be passive about protecting herself and later didn’t defend herself when her boyfriend put her down and hit her.

- Parents were absent because of abandonment, divorce, or death. Losing a parent increased the probability that we wouldn’t receive the emotional and physical affection we needed. Parental addiction often co-exists with and amplifies each dimension of family trouble described here. Single parents were emotionally stressed and frequently struggled financially. Divorce exposed some of us to tough choices between loyalty and closeness, and we sometimes felt compelled to ally ourselves with one or the other parent.

A Feeling of Abandonment

Amanda’s parents divorced when she was ten, after her alcoholic father abandoned the family. Amanda had been very close to him, so she felt alone and forgotten. Her mother struggled financially for years and never remarried. She resented Amanda, who physically resembled her father and served as a reminder of that painful relationship. Even though she desperately needed affection, Amanda grew up feeling that she couldn’t trust anyone.

- Our families had problems with sexual boundaries. Sexual boundaries, or setting appropriate limits on sexual information, talking, or behavior, are always the responsibility of adults, not children. Dr. Alice Miller notes that children have sexual curiosity but don’t engage in adult sexual behavior spontaneously (Thou Shalt Not Be Aware: Society’s Betrayal of the Child). Family sexual boundary problems included the absence of appropriate sexual education; inappropriate or humiliating communications to children about sexuality; parental sexual affairs, exposure to pornography, nudity and covert seduction, inappropriate touching, and sexual abuse. In extreme cases, children were victims of sadistic or violent sexual activity. Sexual violations in families have a profound and enduring destructive impact in terms of identity, self-worth, and future sexual behavior.

Confused Sexuality

It horrified Stan as an early teenager when he learned his mother was having an affair. He witnessed his father publicly confronting his mother and her lover, and he felt overwhelmed and humiliated. At that age, he was emotionally unprepared to understand this event. He was naïve about sex and just noticing girls. His mother’s affair left him with feeling contempt for women, and he degraded women he became sexual with. It shattered his natural developmental acceptance of sexuality.

- Parental Addictions and Entrenched Institutional Systems. Parental addiction often co-exists with and amplifies the seven categories of family trouble described above. In addition, the impact of troubled families is greatly magnified for Native Americans, Native Alaskans, Black Americans, and other indigenous peoples and immigrant groups through chronic exposure to, interaction with, and attempts to meet basic human needs within dysfunctional institutions. Trauma including community dysfunction, multigenerational trauma, institutional racism, abuse during boarding school experiences, cultural assault, poverty, lack of opportunity, inadequate education, job training, and health care deficits.