Enduring Emotional Adjustments from Family Trauma Syndrome

December 20, 2025

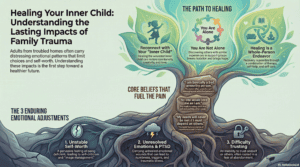

In this chapter I describe three important dimensions of the continuing adult impact of Family Trauma Syndrome for those of us who grew up in troubled homes: Enduring Emotional Adjustments from Childhood: (1) unstable self-worth, (2) unresolved emotions and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and (3) difficulty trusting. These emotional adjustments are distressing, limit our choices, and make us vulnerable to self-defeating life patterns and addictions. During recovery we face these painful emotional states with support and, over time, using new recovery resources, we’re able to overcome these painful feelings.

My name is Lane Lasater, a retired clinical psychologist. In gratitude for the life I have been given, I am sharing everything I learned during my career and personal life here on my website http://www.LaneLasater.com and on my YouTube Channel Life Roadmaps from a Retired Psychologist https://www.youtube.com/@lane205 Each post contains my written material, an AI generated graphic, a 15-17 minute audio summary, and a 5-7 minute video summarizing the material. A printable and fillable PDF “Exercises to Support Recovery from Family Trauma Syndrome” with each exercise I describe in my videos can be downloaded here: Transcending Family Trauma Workbook

1. Unstable Self-Worth

Unstable self-worth is a subtle and pervasive problem that shows up in many forms: lack of confidence, self-criticism, feelings of unworthiness, perfectionism, grandiosity, withdrawal, self-sabotage, and hesitance to take risks. Many of us are afraid to try anything new because we can’t risk humiliation. We find ourselves frequently in a state of anxiety. People in self-help groups describe unstable self-worth as like being “a megalomaniac with an inferiority complex” where we experience dramatic swings between emotional highs and lows.

When we attempt to meet adult challenges and responsibilities with impaired self-worth and a critical internal dialogue, we fear being exposed as inadequate. Shame is one of the most painful dimensions of our unstable self-worth. Gershen Kaufman describes this painful emotion in his book (Shame: The Power of Caring):

“Contained in the experience of shame is the piercing awareness of ourselves as fundamentally deficient in some way as a human being. To live with shame is to experience the very essence or heart of the self as wanting.”

To avoid humiliation, we often arrange our lives to avoid this painful exposure at any cost. We practice “image management,” emphasizing looking good on the outside regardless of our true emotional or family situation. We put up a good front no matter what, but end up feeling lonely and inadequate. In a society that idolizes and competes for external trappings of success, power, youth, wealth, and happiness, many of us experience a “shame gap.” This is the discrepancy between the public image of status, power, confidence, and success we attempt to convey and the private truth about our emotional lives, intimate relationships, and addiction.

Hurting on the Inside

Megan was a successful student who secretly felt unworthy. Her family adopted her as an infant, but she never knew this until a friend told her when she was in high school. Other students then mocked and humiliated Megan. This horrible experience caused deep feelings of hurt, betrayal, and shame. Megan vowed to become a star achiever to show her family and community she was better than they. Her success was empty, however, because underneath her facade she felt deep loneliness and pain. Megan also drank too much and frequently blacked out. Her hidden vulnerability and addiction were inconsistent with the image she tried to convey. When she finally joined Alcoholics Anonymous, Megan could face her pain and learned to validate and respect herself as she was.

There are powerful cultural prohibitions against admitting failure, whether great or small. To recover, however, we must overcome image management and shame. We confront with compassion the truth about ourselves, our lives, and our families as we grow toward well-being. The ingredients of compassion are (1) understanding the powerful family forces that shaped us; (2) recognizing that other people struggle with similar dilemmas, and (3) embracing the hope that we can change our lives for the better.

Recovery Exercise #7: Your Self-WorthUse a 0-10 Scale, where 10 is “very true” about you. I can do what I must do to improve my life. I give myself the benefit of the doubt when I make mistakes. I feel worthy as a person. I’m able to try new things without doing them perfectly. I feel good about how I meet my responsibilities. How I appear to others matches my feelings inside. I feel compassion for myself and my life. I don’t experience big mood swings regularly. |

|

Starting Repair of Your Self-Worth

Your score on this scale can range from 0 to 80. A score of 40 or below suggests that unstable self-worth may be a significant challenge for you. If your score is between 40 and 60, you have moderately stable self-worth. A score between 60 and 80 suggests you have stable self-worth. If you have unstable or moderately stable self-worth, a good way to change this is through practicing kindness to yourself. Using a book of daily affirmations really helps. Each positive recovery choice and action you take adds slightly to your self-worth.

2. Unresolved Emotions and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Like Megan, we may carry unresolved feelings of hurt, disappointment, shame, guilt, loss, anger, or grief from the past. We may not have had the safety and opportunity before now to process the emotional impact of important events of both childhood and adulthood. Feeling unloved or unwanted, experiencing constant conflict, the death or loss of a parent or sibling, family violence, and sexual boundary problems can each create deep emotional wounds, but because we learned to discount the emotional impact of these traumas to protect ourselves, we never faced them.

When we view reality through the defensive shield of discounting, we become emotionally numb with frozen feelings. We either don’t allow ourselves to feel anything, or we prevent ourselves from feeling too deeply because we’re afraid we’ll fall apart. Often, we may become hypersensitive to rejection, conflict, anger, inconsistency, or sexuality. Many of us feel unable to cope with life events that naturally involve setbacks, losses, transitions, challenging emotions, and conflicts. We perceive normal experiences as insurmountable and may conclude our situations are hopeless.

An important task for young adults is to become independent of our childhood families and learn to function in the larger world—sometimes a frightening experience. To postpone leaving home, some of us made rather desperate attempts to change our families for the better, not accepting we couldn’t make them change. After leaving home, we had to learn the difference between rebelling against and being independent of our families. Some of us try desperately not to be like our parents and as the result discard strengths our families provided. Such rebellion reflects our unfinished separation. True separation frees us to choose ways of life that truly suit us.

A Continuum of Traumatic Experiences

The painful experiences children and adults face in troubled families fall on a continuum between difficult life experiences and severe traumatic events. The more severe the experience, the more extreme is the impact. Unfortunately, in some troubled families, children, and adults experience, sometimes over and over, extreme and violent events. The term Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) originally described how people react to extreme events, such as combat, natural catastrophes, or sexual assault. We now know that less dramatic events (particularly repeated events) can also result in PTSD. The mental health diagnostic manual (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-V) identifies the criteria for PTSD in response to trauma as:

(a) experiencing or witnessing either a life-threatening event or a threat to the personal integrity of oneself or others, and (b) accompanied by the experience of perceived intense fear, helplessness, or horror.

We diagnose PTSD when these symptoms continue for more than a month after the actual events. When people face this kind of threat, we have a fight/flight/freeze response. These physiological responses are the body’s attempt to adapt and survive, including a higher heart rate, shallow breathing, and slowing digestion. These autonomic responses prepare the body to survive the physical threat, but emotionally laden memories often emerge later.

Complex PTSD (C-PTSD)

Dr. Judith Lewis Herman introduced the concept of complex PTSD in 1992 to describe the physical and psychological aftermath of people exposed to severe trauma over a long period, not merely in a single incident. Her paper reviewed multiple studies of devastating consequences for survivors of severe situations such as people held in captivity, tortured, and survivors of concentration camps. She noted several important long-term effects that manifested in such survivors:

“Clinical observations identify three broad areas of disturbance which transcend simple PTSD. The first is symptomatic: the symptom picture in survivors of prolonged trauma often appears to be more complex, diffuse, and tenacious than in simple PTSD. The second is characterological: survivors of prolonged abuse develop characteristic personality changes, including deformations of relatedness and identity. The third area involves the survivor’s vulnerability to repeated harm, both self-inflicted and at the hands of others.”

Many of us who grew up in troubled environments can identify with some characteristics that Dr. Herman identified—(a) diffuse somatic, psychological, and behavioral symptoms, (b) character changes in relationships and identity, and (c) vulnerability to repeated harm either self-inflicted or by others. In my personal recovery and professional experience, this explains why many of us seeking professional help have discovered that single psychotherapy approaches are often insufficient and sometimes destructive because when we couldn’t find relief, we were prone to increased self-doubt and despair.

Recovering from family trauma and adverse childhood experiences is a whole person, whole life endeavor. Our multiple symptoms of distress are successfully addressed and overcome using the comprehensive array of psychotherapy, self-help, self-care, and specialized trauma resolution approaches now available, which I describe in Chapter 9.

General Adaptation Syndrome

Dr. Hans Selye (1907-1982) is considered the father of our understanding of stress and its profound connection to well-being and health. In his early research work with lab animals subjected to chronic distress from which they could not escape, he described a predictable process these unfortunate creatures went through which he termed “General Adaptation Syndrome.”

“Selye’s proposal stipulated that stress was present in an individual throughout the entire period of exposure to a nonspecific demand. He distinguished acute stress from the total response to chronically applied stressors, terming the latter condition ‘general adaptation syndrome’, which is also known in the literature as Selye’s Syndrome. The syndrome divides the total response from stress into three phases: the alarm reaction, the stage of resistance and the stage of exhaustion.”

Consistent with Dr. Herman’s description of C-PTSD above, Dr. Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome identifies a complex series of physiological and psychological reactions that take place when people or animals are subjected to chronic distress from which they cannot escape—exactly the situation in which many children find themselves in with their families, often for years. This further validates the research reviewed earlier regarding the long-term behavioral, psychological and health correlates of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

I mentioned early in this book that “recovery does not mean as good as new.” What I’ve learned during my life and in working with many other people who grew up in challenging backgrounds is that we can attain levels of well-being that we never thought possible, but most of us will never recover a tolerance for placing ourselves in situations or around people which touch old wounds. I discuss this in more depth later in Chapters 14 and 15 dealing with Creating Relationships that Support Recovery and Maintaining Your Recovery.

Reminders Trigger Past Traumatic Memories

When we face extreme situations, we store in memory images, sounds and emotions and a play-by-play account of these events. Because our brain can’t take in overwhelming information during extreme trauma, it stores aspects of the event in memory like fragmented pieces of broken glass. When we recall these events, these memories can rush back to awareness and we see, hear, feel, and re-experience exactly what we went through. Situations that sound, look, feel, or smell like the original event trigger memories, thoughts, and feelings that we react to automatically. The common element of these triggered memories is emotional arousal and fear, signaling that the traumatic event is still happening.

When we get triggered by a particular person, sight, sound, smell, or color, it activates each fragmented part of the traumatized memory. Our fight/flight/freeze response may precipitate a panic attack, or we may become immobilized or lash out. The experience can be overwhelming. Even if your experience was less severe than the criteria of extreme trauma above, you may develop PTSD-like symptoms, including the following characteristics.

- Avoidance: We avoid situations and people that trigger us in various ways—by not remembering, feeling detached, numb, or estranged from others, or losing interest in activities we formerly enjoyed. We strive not to re-experience the feelings, thoughts, or body sensations arising when we think about the traumatic situation. We may feel guilty, ashamed, or terrified when we’re reminded of the trauma.

- Re-experiencing the event: The sensory dimensions of a traumatic event can seem to pop out of nowhere, reminding us that the memory is alive and well, except our reaction is out of proportion to the current situation. Flashbacks, sounds, thoughts, memories, and perceptions may arise unexpectedly and we feel like we’re going through the event again. Many people have dreams and nightmares similar to the event and feel intense emotional and physical distress.

Beginning PTSD and Trauma Recovery

Comprehensive and effective recovery strategies are now available for both PTSD and for less severe traumatic events children often experience growing up in troubled families.

In a later post, titled A Wealth of Resources for Recovery, I will describe two powerful therapy resources for moving beyond trauma—multi-modal experiential therapy and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). With effective treatment and support, we’re able to put our painful and traumatic experience into the proper perspective. Processing and understanding such painful experiences allow us to move on with our lives and integrate painful memories. With healing, these will always be unfortunate or even tragic memories, but they no longer have the power to dominate our lives.

Recovery Exercise #8: Your Unresolved Emotions and PTSD |

| Use a 0-10 Scale, where 10 means “very true” about you. |

| 1. I went through experiences growing up (or in adulthood) that I haven’t let myself feel. |

| 2. I overreact emotionally to situations that touch old feelings. |

| 3. I’m better off not expecting too much, so I won’t get disappointed if things don’t work out. |

| 4. I become depressed, angry, or fearful without really understanding why. |

| 5. I don’t understand what I really feel and need. |

| 6. I avoid people who remind me of others from the past. |

| 7. I’m afraid to let myself feel too deeply because I might fall apart. |

| 8. I try to avoid situations that might trigger old memories. |

Unresolved Emotions and PTSD Total |

| Your score on this scale can range from 0 to 80. Any single item scored at 7 or above suggests an issue to deal with during recovery. An overall score below 25 suggests that unresolved emotions may not deeply trouble you. A score of 25-50 implies unresolved feelings moderately interfere with your life. A score of 50 or above suggests significant distress, and it may be helpful to see a professional for support with unresolved feelings. |

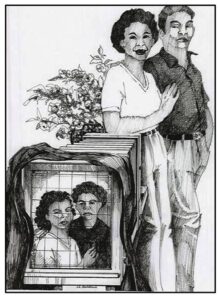

Image 4 portrays our enduring emotional adjustments from childhood.

Healing Our Inner Children: An old-fashioned camera reveals the little boy or girl hidden behind our adult trappings of affluence and success. We must reconcile ourselves with these inner children who carry the memories of childhood losses, hurts, and disappointments. As our inner children heal, they release the tremendous resources of our childhood selves. Then, we rediscover the spontaneity, humor, creativity, tenderness, and love that are the natural experiences of childhood.

3. Difficulty Trusting Ourselves and Others

Singly or in combination, unstable self-worth, unresolved emotions, and PTSD limit our ability to trust ourselves, others, and the world at large. Many of us grow up not believing we can create meaningful lives, form lasting and satisfying relationships, and find a fulfilling place for ourselves in the world. We may enter romantic relationships fearing abandonment. We become preoccupied with image management and shame about our histories and inner lives, and create an invisible distance from other people, who feel pushed away and then withdraw. Thus, we end up alone, telling ourselves we knew all along this would happen and must deserve it.

Acting from unstable self-worth, we sometimes enter and remain in relationships with people who don’t treat us well. We don’t know how to resolve relationship conflicts because we’re afraid of anger, lack awareness of our needs, and find it hard to express our feelings honestly. Unfinished separation from our childhood families drains the energy we have for adult relationships. The combined result of these emotional adjustments is that we often live in a state of fear. Dr. Peter Ossorio describes our basic fear is, “This world doesn’t have a place for me, as me.” (What Actually Happens: The Representation of Real-World Phenomena).

Dr. Patrick Carnes describes three core beliefs that underlie all addictive behaviors (Out of the Shadows: Understanding Sexual Addiction):

- I am basically a bad, unworthy person.

- No one would love me as I am.

- My needs will never be met if I must depend on others.

Beginning to Trust

With such desperate feelings inside, we enter adulthood determined to escape our childhood dragons. Many of us absorb many painful life experiences before accepting we must ultimately confront these feelings we fear. Discovering we can connect through self-help groups with many other people who have been through experiences like our own brings us into the human fold. We don’t have to face our dragons alone, and with the support of these recovery allies, we never have to be alone and hopeless with our pain again.

Ryan’s Emancipation

Ryan met a woman he liked after college but in describing himself said: “I don’t trust my decisions. I feel bad about how I’m running my life. My self-worth is poor. My family was strict, and I didn’t develop my own ideas. My parents didn’t approve of anything I did, so I rebelled inside, but I went along with what they wanted for me because inside I felt lost. They wanted me to become a lawyer, but I’m not cut out for that. I’m more interested in being a writer.”

Ryan’s Enduring Emotional Adjustments

Ryan felt debilitated by this childhood environment of rejection and criticism. He needed support, guidance, and trust as he sought to become independent and find his appropriate place in the world, but felt that he had to adapt and become invisible to survive in his family.

He comforted himself by retreating into books and daydreams, and his interest in being a writer grew out of these childhood activities. He used marijuana to retreat into fantasy when life seemed too painful. As a young adult, Ryan didn’t know himself well and hadn’t gained confidence through trial-and-error decision making. Ryan yearned to trust his feelings about what was right for him, but he needed support.

Ryan’s Healing Process

As he recovered, Ryan learned to be compassionate with himself about the process of his life. “I did pretty well, even though my parents didn’t accept me. I’m ready to move on and have the life I want.” As a starting place, he discontinued all drug use. Later, he chose friends who supported him being true to himself. He recognized he needed acceptance and appreciation from his family of choice.

At work, Ryan recognized he expected people to treat him the way they had treated him at home. By presenting himself in a self-depreciating way, he inadvertently set himself up for this. As he felt better about himself, he presented himself more confidently at work and people respected him. Ryan pursued the woman he was interested in with his eyes open, with no illusion she could offset his past hurts. As his new life took shape and his parent’s inability to accept him no longer preoccupied Ryan, he stopped resenting their failings and created a support system that validated who he was.