Childhood Survival Strategies in Troubled Families

December 19, 2025

Ingenious Childhood Solutions to Impossible Situations

This post explains the ingenious strategies that children develop in order to survive in troubled homes. We find the roots of our problematic adult behavior in the ways we adjusted to our limiting childhood environments. As children, we survived even extreme difficulties, but often at significant emotional cost. Jael Greenleaf points out in her book (Co-Alcoholic, Para-Alcoholic) that as children we had limited power, experience, or information, and didn’t have the option of leaving our families. Our need to survive prevailed.

Unconsciously, we carry on the emotional and behavioral strategies that were often ingenious solutions to our childhood predicaments. Our survival strategies may sometimes enhance our adult situations, but frequently create fresh problems. For example, as children, when it was overwhelming to feel the emotional impact of certain events, we shut down our feelings to preserve the illusion that things were okay. As adults, however, when we’re out of touch with our emotions, we may ignore critical information needed to guide decisions. When we habitually suppress our emotions, we become emotionally numb. Thus, one important goal in recovery from family trauma is learning to feel again, and moving from illusion-based to self-awareness-based decisions.

Part of our new compassionate perspective on ourselves is accepting that we had to make the best of our difficult childhood situations. This chapter describes the resourceful (although costly) childhood strategies we relied upon.

My name is Lane Lasater, a retired clinical psychologist. In gratitude for the life I have been given, I am sharing everything I learned during my career and personal life here on my website http://www.LaneLasater.com and on my YouTube Channel Life Roadmaps from a Retired Psychologist https://www.youtube.com/@lane205 Each post contains my written material, an AI generated graphic, a 15-17 minute audio summary, and a 5-7 minute video summarizing the material. A printable and fillable PDF “Exercises to Support Recovery from Family Trauma Syndrome” with each exercise I describe in my videos can be downloaded here: Transcending Family Trauma Workbook

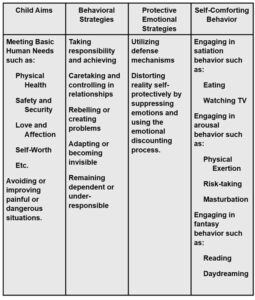

The figure below presents the aims, behavioral strategies, protective emotional strategies, and self-comforting behavior we developed growing up in troubled family systems. The term “strategy” does not imply that we planned these ways of coping. Our behavior in our troubled family resulted both from being cast in certain roles by the family and from our attempts to make things better. For instance, older children often take responsibility and achieve. As older siblings leave home, younger children may take over these roles.

Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse (Another Chance: Help and Hope for the Alcoholic Family) and Dr. Claudia Black (It Will Never Happen to Me) identified common behavioral strategies in working with alcoholic family systems The following strategies apply to children in many troubled families:

Taking responsibility and achieving

Caretaking and controlling in relationships

Rebelling and being a lightning rod

Adapting or becoming invisible

Remaining dependent or under-responsible

Recovery Exercise # 4: Your Childhood Behavioral Strategies

You may have employed different strategies at different times as your family changed or as older siblings left home. But use the following scales to identify strategies you relied upon most heavily while growing up. Rate each of statement using a 0-10 scale: 0 = very untrue of me, 4 = moderately untrue of me, 6 = slightly true of me, 8 = moderately true of me and 10 = very true of me.

Taking Responsibility and Achieving

My responsibilities as a child went beyond what I could handle.

A major way I felt good about myself was by being responsible.

I tried hard and did well in school or in activities like sports, clubs, or jobs.

I felt like a failure if I didn’t do well at something.

Caretaking and Controlling in Relationships

I took (or was assigned) responsibility for other family members as a child.

I counseled or helped one or both of my parents with their problems.

I gave advice or orders to my parents or siblings to make things go better in the family.

I learned to be a good listener, and other people came to me for help.

Rebelling or Being a Lightning Rod

I got in trouble at home because I wouldn’t go along with things I thought were wrong.

I raised issues that other family members felt but didn’t acknowledge.

I rebelled as a child and did destructive things to me or others.

I got into trouble at school and in the community through acting out.

Adapting and Becoming Invisible

I spent time alone as a child because that was more comfortable than being with my others.

The best thing to do was to keep quiet and let things blow over, so I tried to become invisible.

I hoped someone would seek me out and care about me because I felt so lonely.

Family members acknowledged me for not being a bother, even though I needed more attention.

Remaining Dependent or Under-Responsible

My parents didn’t encourage me to become independent and responsible.

One or both of my parents did things for me I needed to do for myself.

Family discipline was loose, and I got away with things I shouldn’t have.

I learned to manipulate or con others into doing things for me.

Your Childhood Behavioral Strategy Scores

Add up your scores for each pattern, which can range from 0 to 40. A score of 20 or above shows you strongly relied upon a particular strategy. You’ll use this information later as you assess whether your strategies progressed into self-defeating life patterns as an adult.

Protective Emotional Strategies

As children, we had to protect ourselves emotionally to maintain equilibrium as we faced the possibility of emotional abandonment or other family disaster. Our most basic defense as children against painful emotional or environmental developments was to deny them. Dr. Peter Ossorio pointed out, “If seeing things as they are puts us in an impossible position, we choose not to see things as they are” (What Actually Happens). By this denial, we bought time (perhaps years) until we could finally understand and integrate those events. Unfortunately, the longer we don’t face, understand, and integrate these painful realities, the longer we suffer from them.

Jacqui Lee Schiff clearly described how we use denial as, “emotional discounting” (All My Children). She identified four levels of discounting we used to spare ourselves from confronting potentially devastating emotional situations when we didn’t have the resources to face these painful truths:

- We discount the existence of a problem.

- We discount the significance of a problem, downplaying its intensity or importance.

- We discount the possibility of changing a problem.

- We discount our own abilities and blame ourselves.

Surviving Fear

Jennifer, a teenager, felt trapped in her family. Her parents fought bitterly and pulled her into their conflicts. Jennifer described these violent scenes in an unemotional manner because she had regularly discounted the intensity and significance of these family crises. She felt helpless to change the situation, and although she wanted to leave home, she felt guilty about leaving behind people she loved. Jennifer criticized herself and concluded she was a burden to her parents and part of the cause of their problems. As a first step in recovery, Jennifer recognized that her parents’ problems were of their own making and she couldn’t change them. She saw she had discounted her feelings and needs in order to survive. As Jennifer recognized the extent of her fear, she moved in with an aunt and uncle with whom she felt safe.

Unfortunately, we continue to discount feelings after leaving our troubled families. As adults, this discounting contributes to entrapment in unsatisfying situations. As we overcome self-defeating behavior strategies and addictions during recovery, we re-examine past family situations and recognize their true emotional significance. As we develop a new and honest emotional perspective on the past, we’re more able to evaluate present situations clearly and act with greater emotional freedom.

Recovery Exercise #5: How You Use Discounting

Identify how you may use discounting in dealing with problems. A good way to do this is to keep a daily log for a week for self-observation. Examine the events of the day and identify times when you discounted your feelings. Also, consider the events of childhood. Today or as a child, did you discount the existence of a problem, discount its intensity or significance, discount the possibilities for change, or discount your own ability and blame yourself?

Be conscious of situations in which you say, “No problem,” “I didn’t even notice,” “That’s okay,” “No big deal,” “I don’t care,” “There is nothing I can do about it,” “I guess I deserved it,” or “I can’t do anything right.” Notice the subtle distress cues you get inside when you discount your feelings. Maybe that bothered you. Maybe there is something you can do about it. Maybe it wasn’t your fault. Stopping habitual discounting is part of the recognition process that prepares you to take positive action in your life.

As I mentioned in my recovery story in Chapter 2, I discovered my emotional discounting about my childhood family when I joked to therapist colleagues about trying to intervene in my parent’s violent arguments, and they responded with silence. Until that moment, I hadn’t recognized the emotional significance of what I was saying—but these friends did. I felt humiliated and ashamed, but thankfully this group of people didn’t take part in my denial. I was using a psychological defense called “gallows humor” to protect against my genuine feelings by making light of what was a tragic situation. Many children from troubled families use gallows humor, trying to cope with painful and overwhelming family realities.

Self-Comforting Behavior

We comforted ourselves as children using whatever means were available. Drs. Harvey Milkman and Stanley Sunderwirth (Craving for Ecstasy) categorize the self-comforting actions people use into three neuro/psychological categories: satiation, arousal, and fantasy. Sleeping, eating, and watching television are examples of satiation behaviors. Arousal behavior includes intense exciting video games, intense exercising, masturbation, and physical risk-taking. Fantasy behavior includes reading comic books, pulp novels, or daydreaming. The childhood self-comforting strategies we used connect to the kinds of addiction we may turn to as adults.

Recovery Exercise #6: Your Self-Comforting

How did you comfort yourself as a child? Rate the actions below from 0 to 10, with 0 showing low reliance on and 10 showing heavy reliance: eating, sleeping, watching television, physical exercise, video games, masturbation, physical risk taking, reading, daydreaming, and other self-comforting behavior ____________________________?